Tampereen Normaalikoulussa (ja varmaan muissakin kouluissa) on käytössä pukeutumiskoodi.

Oikeastaan siellä on opettajille muistaakseni oma pukeutumiskoodi myös,

mutta nyt tarkoitan oppilaiden pukeutumiskoodia. Tarkemmin sanottuna päähineen (joiksi lasketaan ainakin lippikset, pipot ja huput) käyttökieltoa sisätiloissa.

Etenkin

(aineen)opettajaksi opiskelevan näkökulmasta tämä on erikoista, koska

kyseessä on harjoittelukoulu, jossa tulevia opettajia koulutetaan. Tulevia opettajia opetetaan samalla siis noudattamaan ylläpitämään tätä pukeutumiskoodia.

Tämä on nähdäkseni ristiriidassa muun opettajien saaman opetuksen

kanssa, jossa puhutaan sellaisista asioista kuin kasvattaminen

kriittiseen ajatteluun, yhteiskunnalliseen osallistumiseen ja

aktiivisuuteen, sekä painotetaan moniarvoisuutta, yksilöllisyyden

arvostamista ja ainakin opettajan roolia jonkinlaisena intellektuellina ja kansankynttilänä.

Tällainen pukeutumiskoodi vaikuttaa kuitenkin perinteiseltä passiivisten, nöyrien ja ajattelemattomien alamaisten

kasvattamiselta, jota nationalisessa hengessä aiempina vuosikymmeninä

ja satoina on pidetty koulun tehtävänä. Samaiseen ajatteluun kuuluu myös

yhteiskuntaluokkien ylläpitäminen, eli köyhien

työläisten lapset pysyköön köyhinä työläisinä, varakkaampien lapsille

olkoon korkeampi asema yhteiskunnassa. Olisihan se kamala, jos

köyhällistökin uskaltaisi ajatella ja olla yhteiskunnallisesti

aktiivista. Koulujärjestelmän toiminta työttömien, sekä lasten ja

nuorten varastona voisi vaikeutua. Ties millä muilla tavoilla voisi yhteiskuntarauha (status quo, eli oikeasti vallanpitäjien valta-asema) järkkyä.

Samalla kun pukeutumiskoodilla kielletään

päähineiden käyttö sisätiloissa lähes kaikilta (tosin naisille ehkä

sallitaan jotkin pukuun kuuluvat päähineet mielenkiintoisena ja

paljastavana poikkeuksena), perinteeseen vedoten, sallitaan epäilemättä kuitenkin joillekin toisille tiettyjen päähineiden pitäminen uskontoon, kulttuuriin tai toisiin perinteisiin vetoamalla. Samalla relativistisella

tavallahan perustellaan myös tyttöjen ympärileikkausta, joten eipä ole

ihme jos sitä päähineasiassakin käytetään. Mutta vakuuttaako tuo

argumentti ketään? Ja missä suhteessa se on esimerkiksi

perustuslakiimme? Perustuslain mukaanhan Suomessa kaikki ovat tasa-arvoisia

riippumatta muun muassa sukupuolesta ja uskonnosta tai vakaumuksesta.

Jos kuitenkin uskonnollinen päähine sallitaan, mutta uskonnotonta hattua

ei, osoitetaan koululaisillekin selvästi kuinka toiset ihmiset ja asiat vain ovat eriarvoisia. Hienoa kasvatustyötä kouluilta todellakin.

Olen

tämäntapaisia ajatellut jo aika kauan, enkä voi uskoa olevani ainoa tai

edes ensimmäinen näin ajatteleva. Mistä sitten johtuu että tämä

käytäntö kouluissa kuitenkin jatkuu? Ovatko intellektuellit eli

toisinajattelijat opettajien keskuudessa edelleen niin harvoja poikkeuksia?

Friday, November 18, 2011

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Mainoksista hyötyäkin

Olen hyvin pitkään vältellyt mainoksia. Ovessani on noin kymmenen vuotta ollut ilmaisjakelukielto, enkä yleensä katsele mainoksia niistäkään lehdistä joita minulle tulee. Selaan kyllä nykyään jonkun kauppaketjun tms. lehteä, jotka minulle nimellä tulevat, koska olen ketjun kortin omistaja, mutta hyvin nopeasti, koska lehdessä ei juuri koskaan näytä olevan hiukkaakaan kiinnostavaa sisältöä. TV-mainoksia en ole katsellut sen jälkeen kun hankin tallentavan digiboksin (se on niitä ensimmäisiä lajiaan), koska katson ohjelmat vain tallennettuina, jotta voin hypätä mainoskatkojen yli.

Viime aikoina olen muutaman kerran kuitenkin huomannut, että mainoksien seuraamisesta olisi joskus hyötyäkin. Olen nimittäin tarvinnut joitain TV:ssä mainostettavia tuotteita, joiden olemassaolosta tai myyntipaikasta en olisi tiennyt mitään, jollei ystäväni olisi niistä kertonut. En myöskään juuri koskaan tiedä mielenkiintoisten TV-sarjojen alkamisesta, koska www.telkku.fi ei niistä erikseen huomauta. Tämän takia en taaskaan ehtinyt huomata Myytin Murtajien aloittaneen uusien jaksojen näyttämisen, ennenkuin sattumalta osuin telkkarin eteen oikeaan aikaan. Onneksi netti auttaa tässäkin. :-)

Viime aikoina olen muutaman kerran kuitenkin huomannut, että mainoksien seuraamisesta olisi joskus hyötyäkin. Olen nimittäin tarvinnut joitain TV:ssä mainostettavia tuotteita, joiden olemassaolosta tai myyntipaikasta en olisi tiennyt mitään, jollei ystäväni olisi niistä kertonut. En myöskään juuri koskaan tiedä mielenkiintoisten TV-sarjojen alkamisesta, koska www.telkku.fi ei niistä erikseen huomauta. Tämän takia en taaskaan ehtinyt huomata Myytin Murtajien aloittaneen uusien jaksojen näyttämisen, ennenkuin sattumalta osuin telkkarin eteen oikeaan aikaan. Onneksi netti auttaa tässäkin. :-)

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

TMI - The New Title

I still haven't come up with a good title for my blog, but walking home from a coffee corner I like to frequent, I decided to use "TMI - The Philosophy of Jouni Vilkka". TMI here means just what it usually means: too much information! I have been told I tend to share too much, so why not use that as my title? The rest of the the title doesn't really refer to the first, but to the general content and subject of my ramblings and musings here. Or whatever category my writings tend to fall into.

A listing of the most important topics touched upon in my blog can be seen on the top of the main page of my blog. The clever, and those who speak Finnish, can also find a listing of the most important blog entries on my home page.

A listing of the most important topics touched upon in my blog can be seen on the top of the main page of my blog. The clever, and those who speak Finnish, can also find a listing of the most important blog entries on my home page.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Pelitkö aiheuttavat väkivaltaa?

Tiede -lehden uutisen perusteella etsin artikkelin

"The Effect of Video Game Competition and Violence on Aggressive Behavior: Which Characteristic Has the Greatest Influence?"

Kirjoittajat Paul J. C. Adachi and Teena Willoughby, Brock University, Kanada.

PDF täällä.

Tutkimuksen mielenkiintoinen, mutta näin jälkikäteen ei ollenkaan yllättävä tulos on se, että aggressiota lisää ilmeisesti lähinnä tietokonepelien kilpailullisuus, ei niinkään väkivaltaisuus.

Ja miettikääpäs sitten urheilua, urheilun seuraajia, yms. ja heidän käytöstään etenkin urheilutapahtumien yhteydessä tai niihin liittyen. Ja verratkaapa sitten iltamyöhään kotona tietsikkansa ääressä virtuaalihahmoja lahtaaviin nörtteihin. Kummat vaikuttavat todennäköisemmin aggressiivisemmilta noin mielikuvien perusteella? Pitääkö minun oikeasti etsiä tutkimustuloksia?

Tai ajatelkaa vaikka kouluaikojanne, jos niitä muistatte. Kummat enemmän käyttäytyivät väkivaltaisesti, aggressiivisesti, tai muuten vaan törkeästi - nörtit vai urheilullisemmat tyypit? Eivätköhän jenkkien teinileffojen stereotypiat ole tässä aika realistisia: urheilijatyypit ovat nimenomaan niitä kiusaajia ja öykkäreitä aika helvetin paljon todennäköisemmin kuin nörtit.

Jos siis jotain pitää kieltää, kielletään kaikenlainen kilpailu. :-)

"The Effect of Video Game Competition and Violence on Aggressive Behavior: Which Characteristic Has the Greatest Influence?"

Kirjoittajat Paul J. C. Adachi and Teena Willoughby, Brock University, Kanada.

PDF täällä.

Tutkimuksen mielenkiintoinen, mutta näin jälkikäteen ei ollenkaan yllättävä tulos on se, että aggressiota lisää ilmeisesti lähinnä tietokonepelien kilpailullisuus, ei niinkään väkivaltaisuus.

Ja miettikääpäs sitten urheilua, urheilun seuraajia, yms. ja heidän käytöstään etenkin urheilutapahtumien yhteydessä tai niihin liittyen. Ja verratkaapa sitten iltamyöhään kotona tietsikkansa ääressä virtuaalihahmoja lahtaaviin nörtteihin. Kummat vaikuttavat todennäköisemmin aggressiivisemmilta noin mielikuvien perusteella? Pitääkö minun oikeasti etsiä tutkimustuloksia?

Tai ajatelkaa vaikka kouluaikojanne, jos niitä muistatte. Kummat enemmän käyttäytyivät väkivaltaisesti, aggressiivisesti, tai muuten vaan törkeästi - nörtit vai urheilullisemmat tyypit? Eivätköhän jenkkien teinileffojen stereotypiat ole tässä aika realistisia: urheilijatyypit ovat nimenomaan niitä kiusaajia ja öykkäreitä aika helvetin paljon todennäköisemmin kuin nörtit.

Jos siis jotain pitää kieltää, kielletään kaikenlainen kilpailu. :-)

Lapsen kasvattajan tärkein velvollisuus

"Annetaan lasten olla lapsia" implikoi, ettei kasvateta heitä kohti

aikuisuutta. Se on varsinaisen pahoinpitelyn jälkeen kai epäeettisin

teko, mitä kasvattaja voi tehdä. Hänen velvollisuutensa on nimenomaan

ohjata tähän pahaan maailmaan syntynyt lapsi potentiaalinsa

mahdollisimman hyvin toteuttavaksi aikuiseksi, joka osaa sitten

itseohjautuvasti toteuttaa itseään ja edistää yleistä hyvää.

Mielestäni kasvattajan tehtävä (kasvattajana) on nimenomaan (mielestäni itsestäänselvästi) kasvattaa lasta. Siis ei yrittää säilyttää lasta sellaisena kuin se on, vaan auttaa tätä kehittymään.

Olen monta kertaa kuullut (lähinnä tai ainoastaan äitien) valitusta, jonka olen tulkinnut niin, että he haluaisivat pitää lapsensa lapsina ja hoidettavinaan. Sellainen osoittaa mielestäni aika äärimmäistä itsekkyyttä. Hankkisivat vaikka koiran mieluummin. Koiraa saisi sitten helliä ja pitää lapsena sen koko eliniän. Ihmisen kasvattaminen on ihan eri juttu.

Ikävä kyllä ainakin osa lasten huoltajista jättää kasvattamisen lähes kokonaan koulun ja harrasteohjaajien tehtäväksi. Jotkut vanhemmat yrittävät hidastaa lastensa kehittymistä kohtelemalla heitä kuin pikkulapsia, riippumatta lastensa iästä ja kehitysvaiheesta. Tämä on sitä toimintaa, jota sanoin yllä ehkä pahoinpitelyn jälkeen pahimmaksi epäeettiseksi toiminnaksi, johon kasvattaja voi syyllistyä.

Lapset eivät itsekseen kovinkaan hyvin kehity aikuisiksi ihmisiksi. Lapsia täytyy aktiivisesti kasvattaa aikuisuuteen ja ihmisyyteen. Jos kasvattaja vain "antaa lasten olla lapsia", syyllistyy tehtäviensä laiminlyöntiin ja suorastaan lastensa tai kasvatettaviensa heittellejättöön.

Mielestäni kasvattajan tehtävä (kasvattajana) on nimenomaan (mielestäni itsestäänselvästi) kasvattaa lasta. Siis ei yrittää säilyttää lasta sellaisena kuin se on, vaan auttaa tätä kehittymään.

Olen monta kertaa kuullut (lähinnä tai ainoastaan äitien) valitusta, jonka olen tulkinnut niin, että he haluaisivat pitää lapsensa lapsina ja hoidettavinaan. Sellainen osoittaa mielestäni aika äärimmäistä itsekkyyttä. Hankkisivat vaikka koiran mieluummin. Koiraa saisi sitten helliä ja pitää lapsena sen koko eliniän. Ihmisen kasvattaminen on ihan eri juttu.

Ikävä kyllä ainakin osa lasten huoltajista jättää kasvattamisen lähes kokonaan koulun ja harrasteohjaajien tehtäväksi. Jotkut vanhemmat yrittävät hidastaa lastensa kehittymistä kohtelemalla heitä kuin pikkulapsia, riippumatta lastensa iästä ja kehitysvaiheesta. Tämä on sitä toimintaa, jota sanoin yllä ehkä pahoinpitelyn jälkeen pahimmaksi epäeettiseksi toiminnaksi, johon kasvattaja voi syyllistyä.

Lapset eivät itsekseen kovinkaan hyvin kehity aikuisiksi ihmisiksi. Lapsia täytyy aktiivisesti kasvattaa aikuisuuteen ja ihmisyyteen. Jos kasvattaja vain "antaa lasten olla lapsia", syyllistyy tehtäviensä laiminlyöntiin ja suorastaan lastensa tai kasvatettaviensa heittellejättöön.

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Twelve posts on The Phenomenon of Religion

A while back I read The Phenomenon of Religion. A Thematic Approach by Moojan Momen, published by Oneworld Publications, 1999. Here is a list of all the 12 commentaries on that book that I have previously posted in my blog, in chronological order:

1. Thematically about religion

2. Eastern and Western religions

3. Features of a Religious Experience

4. Pathways to Religious Experience

5. Faith and Belief (and Superstition)

6. Acquisition of Religious Belief

7. Religious Conversion

8. The Religious Life

9. Trance and Religious Experience

10. The Origins of the Hadith

11. Fundamentalism and Liberalism

12. Modernism and Religion

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam (in 8 parts)

Here are the links to all the 8 texts about a book concerning Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam that I have previously posted in my blog (in chronological order):

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 1

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 2

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 3

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 4

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 5

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 6

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 7

Modernism and Fundamentalism in Islam. Part 8

Journalismin puutteista

Tämä nyt on jo aika usein soitettu levy, mutta koska se on niin tärkeä, niin soitetaan nyt vielä kerran:

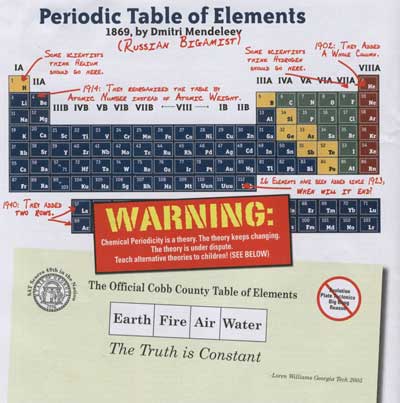

Etenkin USA:ssa, mutta ehkäpä muuallakin, on typerästi korostunut sellainen näkemys, että "objektiivinen journalismi" esittää aina "asian molemmat (2) puolta", eli jonkun asian puolesta ja vastaan. Aihepiiristä on ollut USA:ssa keskustelua (ainakin Skeptical Inquirer -lehdessä) jo pitkän aikaa.

Tuo ajatteluhan sortuu nimittäin väärään dikotomiaan (miksi 2 ja vain 2 näkemystä asiasta?), sekä johtaa kyvyttömyyteen arvioida eri näkemysten painoarvoa ja argumentaatiota (siis journalistin toimesta). Tämä tietysti sopii relativistiseen ajatteluun, jonka mukaan mitään totuutta ei olekaan, mutta tämmöinen naivius ei oikein sovi aikuisille. Siitä seuraa, että lehdissä yms. esitetään kuin saman arvoisina vaikkapa evoluutio ja kreationismi, ihmisten aiheuttama ilmastonmuutos ja sen kieltäminen, yms.

Lukijan tai katsojan tehtäväksi jää vain valita kummasta tykkää enemmän. Yleensähän asiat esitetään niin suppeasti ja pinnallisesti, ettei esitysten perusteella voi niiden uskottavuutta arvioida, eikä useimmilla ihmisillä ole kompetenssia muodostaa perusteltuja käsityksiä merkittävistä asioista. Journalisteilla pitäisi ammattinsa puolesta olla (siis sitä pitäisi voida vaatia), mutta eipä näytä yleensä olevan.

Etenkin USA:ssa, mutta ehkäpä muuallakin, on typerästi korostunut sellainen näkemys, että "objektiivinen journalismi" esittää aina "asian molemmat (2) puolta", eli jonkun asian puolesta ja vastaan. Aihepiiristä on ollut USA:ssa keskustelua (ainakin Skeptical Inquirer -lehdessä) jo pitkän aikaa.

Tuo ajatteluhan sortuu nimittäin väärään dikotomiaan (miksi 2 ja vain 2 näkemystä asiasta?), sekä johtaa kyvyttömyyteen arvioida eri näkemysten painoarvoa ja argumentaatiota (siis journalistin toimesta). Tämä tietysti sopii relativistiseen ajatteluun, jonka mukaan mitään totuutta ei olekaan, mutta tämmöinen naivius ei oikein sovi aikuisille. Siitä seuraa, että lehdissä yms. esitetään kuin saman arvoisina vaikkapa evoluutio ja kreationismi, ihmisten aiheuttama ilmastonmuutos ja sen kieltäminen, yms.

Lukijan tai katsojan tehtäväksi jää vain valita kummasta tykkää enemmän. Yleensähän asiat esitetään niin suppeasti ja pinnallisesti, ettei esitysten perusteella voi niiden uskottavuutta arvioida, eikä useimmilla ihmisillä ole kompetenssia muodostaa perusteltuja käsityksiä merkittävistä asioista. Journalisteilla pitäisi ammattinsa puolesta olla (siis sitä pitäisi voida vaatia), mutta eipä näytä yleensä olevan.

Monday, October 3, 2011

Tekstejäni mediakasvatuskurssilta

Olen suorittamassa mediakasvatuksen peruskurssia kirjoittamalla blogiini aihepiirin tekstejä. Tässä luettelo tähän kurssiin liittyvistä postauksistani (julkaisuajan mukaan järjestettynä):

Johdatus mediakasvatukseen

Sanomalehdistä

Koulukiusaamisen uudet muodot

Median kasvattama

Netti ja ystävyys

Minä median käyttäjänä

Kerhot vastauksena lasten liialliselle mediankäytölle?

Mediapaasto

Medialukutaidon reflektointia

Valintoja mediassa

Pari loistavaa sarjista

Kuvia ympärilläni

Journalismin puutteista

(lisätty 2011-10-04)Pelitkö aiheuttavat väkivaltaa?

(lisätty 2011-10-10)Mainoksista hyötyäkin

(lisätty 2011-10-27)Kuvia ympärilläni

Elämismaailmamme on varsin visuaalinen (ainakin ns. länsimaissa, mutta varmaan melko lailla kaikkialla nykyään). Myös tekstit kuuluvat yleensä visuaalisuuteen (pistekirjoitus siitä poikkeuksena), mutta kuvallisuus on puhtaasti visuaalista, sillä kuvaa ei voi (tietääkseni) oikeastaan kokea muuten kuin näkemällä. Tämä visuaalisuuden korostuminen (ehkä jopa ylikorostuminen) on erityisen suuri ongelma näkövammaisten osalta, mutta siihen liittynee muitakin ongelmia. Erityisesti ärsyttävää on se, että luullakseni suurin osa tästä visuaalisuudesta on kaupallista, (yksityis)yritysten markkinointia. Etenkin katunäkymissä tämä on ikävän selvää.

Näkisin kadunvarsilla paljon mieluummin ei-kaupallisia kuvia, vaikkapa taideteoksia, mutta niiden sijaan näen lähinnä mainoskylttejä: yritysten nimiä ja ulkomainoksia. Ainoan vastakohdan niille taitavat tuoda graffitit, jotka taas ovat nähdäkseni vain rumia suttuja -- jos ne jotain viestittävät, en ehkä edes halua tietää, mitä.

Lehdissä, etenkin aikakauslehdissä (jopa Tiede -lehdessä), kuvat vievät suuren osan sivujen pinta-alasta. Monet lehdet on tarkoitettu vain kevyeksi vilkuiltavaksi, eikä vakavammissakaan ole sinänsä haitaksi jos informatiivisten kuvien ohella käytetään joitakin vain lukukokemusta miellyttävämmäksi tekeviä kuvia. Sen sijaan erityisesti naistenlehdet tuntuvat sisältävän suorastaan haitallista materiaalia.

Tarkoitan tietysti nykyään jo paljon (muttei ehkä vielä puhki) puhuttuja kuvia etenkin naisista, mutta myös miehistä, jotka vaikuttavat etenkin nuoriin mieliin haitallisesti. Naistenlehtiä lukevat tytöt voivat saada itsetunto-ongelmia (ja mm. syömishäiriöitä) näistä leikattujen ja meikattujen naisten photoshopatuista kuvista, jotka tavoittelevat sellaisia kauneusihanteita, joihin kuolevainen ihminen ei pysty. Siksi mielestäni pornon ja väkivaltaviihteen sijasta kielletyksi kannattaisi mieluummin asettaa tämä paljon haitallisempi median muoto.

Näkisin kadunvarsilla paljon mieluummin ei-kaupallisia kuvia, vaikkapa taideteoksia, mutta niiden sijaan näen lähinnä mainoskylttejä: yritysten nimiä ja ulkomainoksia. Ainoan vastakohdan niille taitavat tuoda graffitit, jotka taas ovat nähdäkseni vain rumia suttuja -- jos ne jotain viestittävät, en ehkä edes halua tietää, mitä.

Lehdissä, etenkin aikakauslehdissä (jopa Tiede -lehdessä), kuvat vievät suuren osan sivujen pinta-alasta. Monet lehdet on tarkoitettu vain kevyeksi vilkuiltavaksi, eikä vakavammissakaan ole sinänsä haitaksi jos informatiivisten kuvien ohella käytetään joitakin vain lukukokemusta miellyttävämmäksi tekeviä kuvia. Sen sijaan erityisesti naistenlehdet tuntuvat sisältävän suorastaan haitallista materiaalia.

|

| Tässä esimerkki. Muita voit vaikka tilata täältä. |

Tarkoitan tietysti nykyään jo paljon (muttei ehkä vielä puhki) puhuttuja kuvia etenkin naisista, mutta myös miehistä, jotka vaikuttavat etenkin nuoriin mieliin haitallisesti. Naistenlehtiä lukevat tytöt voivat saada itsetunto-ongelmia (ja mm. syömishäiriöitä) näistä leikattujen ja meikattujen naisten photoshopatuista kuvista, jotka tavoittelevat sellaisia kauneusihanteita, joihin kuolevainen ihminen ei pysty. Siksi mielestäni pornon ja väkivaltaviihteen sijasta kielletyksi kannattaisi mieluummin asettaa tämä paljon haitallisempi median muoto.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Pari loistavaa sarjista

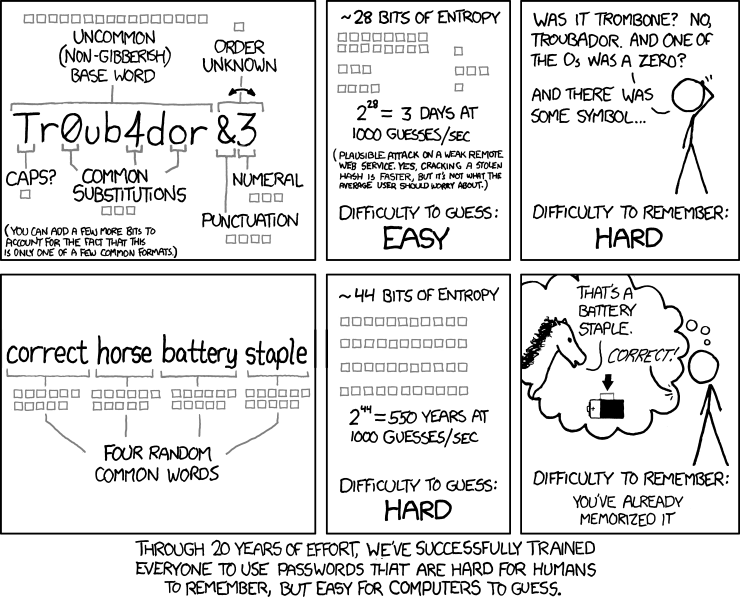

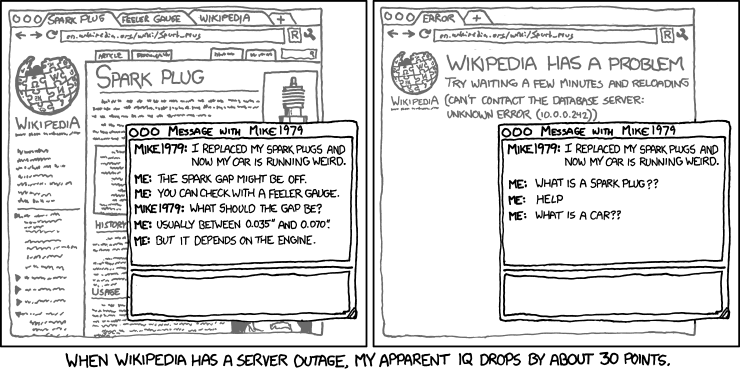

xkcd on monien suosima (ja ehkä kaikkien aikojen ja koko maailman paras) nettisarjis.

Tuo nimi ei muuten ole lyhenne eikä tarkoita mitään.

Tässä sarjiksessa on ollut ainakin joitakin mainioita strippejä (kai tämä on oikea termi?) tähän Mediakasvatus -kurssiin liittyen, jolla olen. Yritän lainata niitä tässä. Klikkaamalla kuvaa saat suurennoksen.

Ensimmäinen ( http://www.xkcd.com/936/ ) liittyy salasanoihin. Kaikkien tietokoneita käyttävien pitäisi ottaa tästä heti opiksi:

Toinen ( http://www.xkcd.com/903/ ) liittyy suoremmin kurssiin, erityisesti tiedon uuteen luonteeseen, mutta myös lähdekritiikkiin ja Wikipediaan:

Tuo nimi ei muuten ole lyhenne eikä tarkoita mitään.

Tässä sarjiksessa on ollut ainakin joitakin mainioita strippejä (kai tämä on oikea termi?) tähän Mediakasvatus -kurssiin liittyen, jolla olen. Yritän lainata niitä tässä. Klikkaamalla kuvaa saat suurennoksen.

Ensimmäinen ( http://www.xkcd.com/936/ ) liittyy salasanoihin. Kaikkien tietokoneita käyttävien pitäisi ottaa tästä heti opiksi:

Toinen ( http://www.xkcd.com/903/ ) liittyy suoremmin kurssiin, erityisesti tiedon uuteen luonteeseen, mutta myös lähdekritiikkiin ja Wikipediaan:

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Valintoja mediassa

Ensin urputus: termin "media" yksikkömuoto on "medium". "Media" on siis jo monikko. "Mediat" on jotain aika outoa minun korvilleni. No se siitä. Olen liian humaltunut muistaakseni edes mitä minun tästä piti oikeastaan sanoa. Soittakaa joku "Red, red wine"... ;)

*

Asiaan. Olen tässä huvikseni ja kyseenalaiseksi hyödykseni ja ehkä harjoitukseksikin tai sitten vain viinin vaikutuksen takia kerännyt Mediakasvatuskurssimme blogeja seurattavakseni. Onneksi suurin osa on samalla alustalla toimivia, joten ne on helppo ottaa stalkkauksen kohteeksi. Osa on tehty muilla ja muissa systeemeissä. Niistä joitakin saa silti helposti seurattua. Joidenkin kohdalla seuraaminen olisi "kohtuuttoman" vaikeata, eli vaatisi jonkun tilin perustamisen tms. Semmoiseen en rupea. Tämän takia en siis seuraa kaikkia kurssin blogeja.

(EDIT: Minulle näyttää kertyneen 49 blogia listalle ja olen niitä kaikkia seurannut, myös kommentoiden ja +1 merkkaillen aika ahkerasti. Melko paljon hommaa se on ollut, enkä tiedä kuinka työekonomisesti järkevä tämä ratkaisu oli. Mutta olipahan mielenkiintoinen kokemus.)

Vastaavia valintoja mediamaailmassa tehdään muuallakin. Tämähän on se syy, miksi FB on niin suosittu, ja Google+ ja muut kilpailijat niin kovien vaikeuksien edessä: on todella vaikea saada suostuteltua ketään "muuttamaan" toiseen systeemiin, jos ei saa varsin suurta osaa suostuteltua kerralla.

*

Asiaan. Olen tässä huvikseni ja kyseenalaiseksi hyödykseni ja ehkä harjoitukseksikin tai sitten vain viinin vaikutuksen takia kerännyt Mediakasvatuskurssimme blogeja seurattavakseni. Onneksi suurin osa on samalla alustalla toimivia, joten ne on helppo ottaa stalkkauksen kohteeksi. Osa on tehty muilla ja muissa systeemeissä. Niistä joitakin saa silti helposti seurattua. Joidenkin kohdalla seuraaminen olisi "kohtuuttoman" vaikeata, eli vaatisi jonkun tilin perustamisen tms. Semmoiseen en rupea. Tämän takia en siis seuraa kaikkia kurssin blogeja.

(EDIT: Minulle näyttää kertyneen 49 blogia listalle ja olen niitä kaikkia seurannut, myös kommentoiden ja +1 merkkaillen aika ahkerasti. Melko paljon hommaa se on ollut, enkä tiedä kuinka työekonomisesti järkevä tämä ratkaisu oli. Mutta olipahan mielenkiintoinen kokemus.)

Vastaavia valintoja mediamaailmassa tehdään muuallakin. Tämähän on se syy, miksi FB on niin suosittu, ja Google+ ja muut kilpailijat niin kovien vaikeuksien edessä: on todella vaikea saada suostuteltua ketään "muuttamaan" toiseen systeemiin, jos ei saa varsin suurta osaa suostuteltua kerralla.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Medialukutaidon reflektointia

Joudun aina välillä häpeämään heikkoja taitojani, koska historiaakin opiskelleena minulla pitäisi olla mainiot tiedonhauan ja lähdekritiikin taidot, mutta usein tunnen olevani niissä huono. En siis ainakaan ole niin hyvä kuin voisin olla. Tämä koskee lähinnä perinteisten tiedotusvälineiden käyttöä.

Toisenlainen epäpätevyyteni liittyy "sosiaalisena" tunnettuihin median muotoihin. Olen kyllä ollut internetin asukas jo kauan ja tämän bloginikin perustin jo 2007. Facebook on käytössä ja muihinkin sosiaalisen median muotoihin olen vähintään tutustunut. Osallistumiseni, siis sosiaalisuuteni, näissä medioissa on kuitenkin hyvin vähäistä. En esim. tee YouTubeen videoita, enkä edes lue toisten blogeja normaalisti kuin harvoin. En ole koskaan kirjoittanut Wikipediaan mitään. Varmasti "lukutaitoni" eli todellinen käyttötaitoni olisi toisenlaista, jos olisin sosiaalisempi netissä.

Tallentavan digiboksin ansiosta seuraan mainoksiakin nykyään erittäin vähän, mikä joskus aiheuttaa jopa tunteen tietämättömyydestä (olen törmännyt tilanteeseen että jotain tarvitsemaani tuotetta on mainostettu TV:ssä, mutten ole ollut tästä tietoinen). Seuraan ylipäätään TV-ohjelmia erittäin vähän: katson vain elokuvia (erityisesti komediat), uutiset, sekä ehkä joskus jotain TV:n komediasarjaa, jos tiedän sellaisesta (uusien sarjojen alkaminen on hankala huomata Telkku.comin sivulla). Olen kyllä jo kauan tiedostanut sarjoissa ja elokuvissa käytettyä tuotesijoittelua, mutta esim. "tosi-TV" ohjelmat saattavat sisältää paljonkin minulle tuntemattomia vaikuttamisen muotoja.

*

No niin. Yritän tässä liittää Picasasta kuvan tekstiäni kaunistamaan, mutta idiootti saitti muuttaa kielen saksaksi, joka on minulle yhtä siansaksaa (vaikka olenkin joskus hieman saksaa muka opiskellut). Vaikeuteni tässä osoittanee ainakin heikkoa mediakirjoitustaitoa. No, laitoin sitten Flickr.com -saitilta tuon "filosofisen" kuvan kun kerran oli helpompaa.

Toisenlainen epäpätevyyteni liittyy "sosiaalisena" tunnettuihin median muotoihin. Olen kyllä ollut internetin asukas jo kauan ja tämän bloginikin perustin jo 2007. Facebook on käytössä ja muihinkin sosiaalisen median muotoihin olen vähintään tutustunut. Osallistumiseni, siis sosiaalisuuteni, näissä medioissa on kuitenkin hyvin vähäistä. En esim. tee YouTubeen videoita, enkä edes lue toisten blogeja normaalisti kuin harvoin. En ole koskaan kirjoittanut Wikipediaan mitään. Varmasti "lukutaitoni" eli todellinen käyttötaitoni olisi toisenlaista, jos olisin sosiaalisempi netissä.

Tallentavan digiboksin ansiosta seuraan mainoksiakin nykyään erittäin vähän, mikä joskus aiheuttaa jopa tunteen tietämättömyydestä (olen törmännyt tilanteeseen että jotain tarvitsemaani tuotetta on mainostettu TV:ssä, mutten ole ollut tästä tietoinen). Seuraan ylipäätään TV-ohjelmia erittäin vähän: katson vain elokuvia (erityisesti komediat), uutiset, sekä ehkä joskus jotain TV:n komediasarjaa, jos tiedän sellaisesta (uusien sarjojen alkaminen on hankala huomata Telkku.comin sivulla). Olen kyllä jo kauan tiedostanut sarjoissa ja elokuvissa käytettyä tuotesijoittelua, mutta esim. "tosi-TV" ohjelmat saattavat sisältää paljonkin minulle tuntemattomia vaikuttamisen muotoja.

*

No niin. Yritän tässä liittää Picasasta kuvan tekstiäni kaunistamaan, mutta idiootti saitti muuttaa kielen saksaksi, joka on minulle yhtä siansaksaa (vaikka olenkin joskus hieman saksaa muka opiskellut). Vaikeuteni tässä osoittanee ainakin heikkoa mediakirjoitustaitoa. No, laitoin sitten Flickr.com -saitilta tuon "filosofisen" kuvan kun kerran oli helpompaa.

Mediapaasto

Tiesin jo etukäteen, että Mediakasvatuskurssin tehtävä pitää päivän mittainen "paasto" eli tauko mediankäytöstä olisi mahdoton. Ajattelin silti ihan oikeasti yrittää yhden päivän ajan käyttää erilaisia tiedotusvälineitä mahdollisimman vähän. Tämä päivä oli eilen.

Huomasin kuitenkin aamupäivällä ruokaillessani, että olin jo hyvän aikaa katsonut elokuvaa. En kuitenkaan lopettanut elokuvan katsomista, koska siinä oli tyylilajilleen poikkeuksellisen mielenkiintoisia asioita (ikävä kyllä loppupuoli elokuvasta sortui kliseisiin). En malttanut myöskään olla tarkastamatta kännykän kautta wikipediasta erästä elokuvassa mainittua termiä ja siihen liittyvää vuosilukua. Minulle oli tullut sähköpostia, jonka lukaisin myös kännykän kautta pikaisesti.

Olin sopinut erään lautapelin pelaamisesta iltapäivällä. Koska en osaa olla tekemättä mitään, enkä keksinyt muutakaan tekemistä odottelun ajaksi, luin Skeptical Inquirerin uusimman numeron loppuun.

Pelaajien saavuttua pelasimme hauskaa lautapeliä nimeltä A Touch Of Evil: The Supernatural Game. Pelin aikana minun täytyi useaan otteeseen lukea sääntökirjaa. Taustalla soitin tapani mukaan tietokoneen kautta levyjä.

Pelaajien lähdettyä juttelin hetken jonkun kanssa gTalk-sovelluksen kautta ja luin Tiede-lehden uusimman numeron loppuun.Aloin masentua, joten katsoin vielä yhden komediaelokuvan.

En siis onnistunut vähentämään mediankäyttöäni juuri ollenkaan (minun täytyi pinnistellä, etten kirjoittaisi tätä blogia jo illalla). Ainoa ero tavalliseen päivään oli se, etten lukenut kurssikirjoja ollenkaan. Tämä ei liene edistystä. Saatan vielä yrittää mediapaastoa uudestaan joku päivä, mutten usko saavani kovin erilaista tulosta aikaiseksi, ellen sitten joudu tilanteeseen, jossa minun on todellakin mahdotonta käyttää tiedotusvälineitä.

Huomasin kuitenkin aamupäivällä ruokaillessani, että olin jo hyvän aikaa katsonut elokuvaa. En kuitenkaan lopettanut elokuvan katsomista, koska siinä oli tyylilajilleen poikkeuksellisen mielenkiintoisia asioita (ikävä kyllä loppupuoli elokuvasta sortui kliseisiin). En malttanut myöskään olla tarkastamatta kännykän kautta wikipediasta erästä elokuvassa mainittua termiä ja siihen liittyvää vuosilukua. Minulle oli tullut sähköpostia, jonka lukaisin myös kännykän kautta pikaisesti.

Olin sopinut erään lautapelin pelaamisesta iltapäivällä. Koska en osaa olla tekemättä mitään, enkä keksinyt muutakaan tekemistä odottelun ajaksi, luin Skeptical Inquirerin uusimman numeron loppuun.

Pelaajien saavuttua pelasimme hauskaa lautapeliä nimeltä A Touch Of Evil: The Supernatural Game. Pelin aikana minun täytyi useaan otteeseen lukea sääntökirjaa. Taustalla soitin tapani mukaan tietokoneen kautta levyjä.

Pelaajien lähdettyä juttelin hetken jonkun kanssa gTalk-sovelluksen kautta ja luin Tiede-lehden uusimman numeron loppuun.Aloin masentua, joten katsoin vielä yhden komediaelokuvan.

En siis onnistunut vähentämään mediankäyttöäni juuri ollenkaan (minun täytyi pinnistellä, etten kirjoittaisi tätä blogia jo illalla). Ainoa ero tavalliseen päivään oli se, etten lukenut kurssikirjoja ollenkaan. Tämä ei liene edistystä. Saatan vielä yrittää mediapaastoa uudestaan joku päivä, mutten usko saavani kovin erilaista tulosta aikaiseksi, ellen sitten joudu tilanteeseen, jossa minun on todellakin mahdotonta käyttää tiedotusvälineitä.

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Kerhot vastauksena lasten liialliselle mediankäytölle?

Kirsi Pohjola ja Kimmo Jokinen ovat kirjoittaneet vuonna 2007 kolumnin "Huoli lasten mediankäytöstä on osin turha", jota tässä lyhyesti kommentoin. Kolumni perustui kirjoittajien tekemään tutkimukseen lasten mediankäytöstä. Heidän mielestään lasten virtuaaliympäristöihin liittyvät pelot ja moraalinen paniikki ovat turhan suuria; asiat ovat pääasiassa hyvin. Suurimmat todelliset ongelmat näyttävät olevan joidenkin koulujen tai luokkien (tarkentamattomat) ongelmat estävät opettajia antamasta yhtä paljon (tai hyvää?) koulutusta ja (media)kasvatusta kuin toisten koulujen tai luokkien opettajat. Myös kodeissa on erilaisia valmiuksia tässä suhteessa, mistä esimerkkinä kirjoittajat mainitsevat lapset, joiden elämä näyttää aika yksipuolisesti pyörivän pelien ja (väkivaltaisten) elokuvien ympärillä.

Mainitut ongelmat ovat varmasti todellisia ja vaikeasti hoidettavia. Kaikilla lapsilla ei vain ole mahdollisuuksia harrastaa erilaisia asioita, eikä heidän vanhemmillaan ehkä ole mahdollisuuksia viettää lastensa kanssa aikaa niin paljon kuin joillain toisilla. Jos tällaisille lapsille (etenkin jos heillä ei ole juurikaan ystäviä IRL) ei määrätä rajoituksia esim. pelaamiselle, ei kai ole ihmekään, jos he viettävät aikansa pääasiassa pelikonsolin, tietokoneen tai TV:n ääressä. Pelkät rajoitukset eivät ole tässä mielestäni mitenkään rajoittavia, vaan vaihtoehtoja on tarjottava, jos rajoituksia tehdään. On turha käskeä lapsi ulos leikkimään, jos ulkona odottaa vain vihamielinen tai ainakin sellaiseksi koettu maailma.

Kummallista kyllä, kolumnissa ei mainittu mitään nettikiusaamisesta, eikä tarpeesta opettaa lapsia käyttämään nettiä ja kameroita ja kännyköitä oikein sekä tiedollisesti että eettisesti. Tähän asiaan liittynee paljon enemmän ongelmia kuin pelkkään pelaamiseen tai TV:n katseluun.

Yksi, en tosin tiedä kuinka realistinen, tapa yrittää korjata vähävirikkeisyyttä niiden lasten osalta, joilla on vain vähän mahdollisuuksia "tosielämän" harrastuksiin ja sosiaalisiin suhteisiin, olisi tarjota koulussa harrastuskerhomahdollisuuksia. Näiden tarkoituksena olisi pääasiassa auttaa lapsia verkostoitumaan ikäistensä kanssa, vaikka eksplisiittisesti esitetty kerhon tarkoituskin (esim. pelikerho) on tietysti toteutettava. Vaikeutena on kuitenkin saada aikaan lämmin, hyväksyvä, vastaanottava, inklusiivinen, siis sanalla sanoen ystävällinen ilmapiiri, jotta ujoimmat ja sosiaalisesti heikkolahjaisimmatkin saataisiin mukaan.

|

| Ainakin joissakin kouluissa pelikerhoja jo harrastetaankin. Kuva on Varissuon koulusta, Turusta. |

Jos tällainen toiminta olis mahdollista toteuttaa (toivottavasti sellaiseen saadaan jotenkin riittävä rahoitus kaikkialla), sillä voisi olla suurikin vaikutus juuri kaikkein huonoimmassa asemassa olevien lasten kohdalla. Rahoituksen oikeuttamiseksi tähän voitaisiin vaikka yhdistää jotain opetuksellista, mutta vain jos lapset saadaan hyväksymään se ja kerho saadaan pidettyä selvästi hauskana ja (varsinaisesta) koulusta irrallisena. Tärkeintä on ilo ja omaehtoinen toiminta ystävällisessä ilmapiirissä.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Minä median käyttäjänä

Kurssilla annettiin tämmöinen tehtävä, jota yritän nyt suorittaa:

Seuraa jälleen omaa toimintaasi median käyttäjänä. Oletko vastaanottaja, sisältöön tarttuva kriitikko, muodon analysoija vai vaihtoehtoisten tapojen suunnittelija? Vai vaihteletko näitä tapoja? Miten nuo suhtautumistavat mediaan näkyvät käytännössä toimintana?

Erityisesti kiinnitä huomiota niihin tilanteisiin, joissa on useampia henkilöitä median äärellä.

Viimeinen kohta tuottaa heti vaikeuksia. Olen median äärellä yhdessä muiden kanssa lähinnä luennoilla, tai nykyään myös koulun oppitunneilla opettajakoulutuksen yhteydessä. Median määrittely on myös edelleen ongelma. Olen pelinjohtajana roolipelissä, jossa pelaajia on (lisäkseni) neljä. Pelimateriaali, jota käytän, on pääosin kirjamuodossa, tosin jonkin verran lisään siihen kirjoittamalla itse ja etenkin etsimällä sopivaa materiaalia netistä. Tässä tilanteessa olen vastaanottaja, joka kirjoista ja netistä suodattaa pelaajille valikoiden materiaalia.

Facebookissa ja jossain määrin myös täällä blogissani olen suunnittelija ja tuottaja, sisällön kriitikko ja ehkä joskus myös muodon analysoija. Sosiaalisesta mediasta kun kerran puhutaan, niin siinä mielessä näissä tapauksissa median äärellä on useampia ihmisiä. Sisällön osalta saatan kommentoida esimerkiksi epäuskottavan oloisia väitteitä, tai tulkintaa jostain asiasta. Muodon tai paremminkin tyylin osalta olen joskus esittänyt kommentteja jopa Facebookissa, mutta enemmän keskustelualueilla ja sähköpostilistoilla. Eniten kai kuitenkin olen vastaanootajana näissä kaikissa. Selvästi kuitenkin siis vaihtelen näitä tapoja.

Netti ja ystävyys

Lueskelin taas viinilasi kädessä teosta Kynäslahti, Kupiainen & Lehtonen (toim.): Näkökulmia mediakasvatukseen. Mediakasvatusseuran julkaisuja 1/2007. Siinä on artikkeli nimeltä "Tunteella ja järjellä nettiin – Internetissä tarvitaan uudenlaisia mediataitoja" (kirjoittajina Suvi Tuominen ja Anu Mustonen). Ehkä johtuu osittain viinistäkin, mutta nyt alkoi kiinnostaa.

Artikkelissa kerrotaan tutuista asioista, joihin haluan tehdä muutaman henkilökohtaisen lisäyksen. Ehkä sitten selvempänä poistan koko tämän tekstin, tai sitten en. Sosiaalisen median yksi puoli on juuri tämä, eli mahdollisuus tehdä itsensä naurunalaiseksi poikkeuksellisen monen ihmisen edessä. Asiaan.

Artikkelissa huomautetaan hyödyllisesti esimerkiksi siitä, että nettiystävyys (ja -rakkauskin) on paitsi jo ihan normaalia, se on myös jollain tapaa parempaa kuin perinteisempi kasvokkaisen elämän ystävyys. Näin siksi, että ihmiset voivat jopa asua vaikka kuinka kauan yhdessä silti oikeasti tuntematta toisiaan. Tämä tuntemattomuus voi sitten tietysti tulla esiin jossain yllättävässä tilanteessa, kun selviää, ettei toinen ajatellutkaan niinkuin oli itse ajatellut. Netin kautta muodostettu ystävyys tai mikä vain suhde on lähes välttämättä tässä erilainen, sillä se perustuu sanalliseen kommunikaatioon aivan toisella tavalla kuin "reaalimaailman" kontaktit. Kun ystävyys perustuu (edelleenkin usein kirjalliseen) keskusteluun, ystävystyvät ihmiset oppivat tuntemaan toisensa paljon paremmin kuin muuten olisi mahdollista.

Olen jopa tätä oivallusta käyttänyt hyväksi siinä, että olen kehottanut avioliitossa olevia kirjoittamaan toisilleen joko perinteisesti paperin tai sitten sähköpostin välityksellä. Teknologioihin (siis myös perinteisiin kynään ja paperiin) liittyvän tietyn etäännyttävän vaikutuksen takia sanallinen kommunikaatio esimerkiksi riitatilanteessa on helpottava jo siksikin, että se auttaa rauhoittamaan voimakkaina vellovat tunteet, joita taas kasvokkainen kommunikaatio ruumiinkielineen vain ruokkisi. Tämä voi tietysti olla haitaksi myönteisten tunteiden osalta, mutta toisaalta sitä voidaan haluttaessa ainakin jonkin verran kiertää. Toisaalta järkevyys on aina parempi kuin voimakkaat tunteet, joten ehkä tätä ei edes pitäisi nähdä ongelmana?

Netin hyödyllisyys ystävyyssuhteissa on tullut omalla kohdallani selväksi jo kauan sitten. Olen nimittäin jo 1990-luvulta lähtien toiminut terapeuttisena ystävänä netin kautta tapaamilleni ihmisille. On vaikea uskoa, että samanlaista suhdetta voisi kovin helposti muodostaa IRL (In Real Life), kuten nettikielellä sanotaan.

Minusta netti on yksi kaikkien aikojen hienoimmista ja parhaimmista keksinnöistä, koska se voi yhdistää ihmisiä ennennäkemättömällä tavalla, sekä tuoda tietoa lähes kaikkien saataville varsin helposti. Tietysti siinä on ongelmansa, niinkuin kaikessa. On kuitenkin tärkeää opettaa jo lapsia (sekä tietysti myös aikuisia) netin käytössä. Tätä varten pitäisi julkaista kunnollinen netin käytön ja netiketin opas, joka olisi mieluiten ilmainen. Siinä opetettaisiin kriittistä suhtautumista nettiin ja tiedonhakua yms., sekä käytössääntöjä ja järkevän toiminnan suosituksia. Siinä kerrottaisiin siis esimerkiksi, ettei nuoren ole järkevää välttämättä esiintyä netissä omalla virallisella nimellään, eikä välttämättä kannata lähettää kavereilleen tai ladata kuvagalleriaan sellaisia kuvia, joita ei haluaisi kaikkien nähtäville. Oleellista olisi selittää, miksi peruskäytössääntöjä on hyvä noudattaa etenkin netissä (mutta muuallakin). Tähän kuuluu myös hyväntahtoisen tulkinnan periaatteen selittäminen ja perustelu. Tietysti siinä pitäisi kertoa myös lakiasiat, eli mikä on laitonta ja mikä ei. Yhtä tärkeää kuitenkin on kertoa ovelista mainonta- ja manipulointikeinoista, joita netin ja muidenkin medioiden kautta voidaan käyttää.

Artikkelissa kerrotaan tutuista asioista, joihin haluan tehdä muutaman henkilökohtaisen lisäyksen. Ehkä sitten selvempänä poistan koko tämän tekstin, tai sitten en. Sosiaalisen median yksi puoli on juuri tämä, eli mahdollisuus tehdä itsensä naurunalaiseksi poikkeuksellisen monen ihmisen edessä. Asiaan.

Artikkelissa huomautetaan hyödyllisesti esimerkiksi siitä, että nettiystävyys (ja -rakkauskin) on paitsi jo ihan normaalia, se on myös jollain tapaa parempaa kuin perinteisempi kasvokkaisen elämän ystävyys. Näin siksi, että ihmiset voivat jopa asua vaikka kuinka kauan yhdessä silti oikeasti tuntematta toisiaan. Tämä tuntemattomuus voi sitten tietysti tulla esiin jossain yllättävässä tilanteessa, kun selviää, ettei toinen ajatellutkaan niinkuin oli itse ajatellut. Netin kautta muodostettu ystävyys tai mikä vain suhde on lähes välttämättä tässä erilainen, sillä se perustuu sanalliseen kommunikaatioon aivan toisella tavalla kuin "reaalimaailman" kontaktit. Kun ystävyys perustuu (edelleenkin usein kirjalliseen) keskusteluun, ystävystyvät ihmiset oppivat tuntemaan toisensa paljon paremmin kuin muuten olisi mahdollista.

Olen jopa tätä oivallusta käyttänyt hyväksi siinä, että olen kehottanut avioliitossa olevia kirjoittamaan toisilleen joko perinteisesti paperin tai sitten sähköpostin välityksellä. Teknologioihin (siis myös perinteisiin kynään ja paperiin) liittyvän tietyn etäännyttävän vaikutuksen takia sanallinen kommunikaatio esimerkiksi riitatilanteessa on helpottava jo siksikin, että se auttaa rauhoittamaan voimakkaina vellovat tunteet, joita taas kasvokkainen kommunikaatio ruumiinkielineen vain ruokkisi. Tämä voi tietysti olla haitaksi myönteisten tunteiden osalta, mutta toisaalta sitä voidaan haluttaessa ainakin jonkin verran kiertää. Toisaalta järkevyys on aina parempi kuin voimakkaat tunteet, joten ehkä tätä ei edes pitäisi nähdä ongelmana?

Netin hyödyllisyys ystävyyssuhteissa on tullut omalla kohdallani selväksi jo kauan sitten. Olen nimittäin jo 1990-luvulta lähtien toiminut terapeuttisena ystävänä netin kautta tapaamilleni ihmisille. On vaikea uskoa, että samanlaista suhdetta voisi kovin helposti muodostaa IRL (In Real Life), kuten nettikielellä sanotaan.

Minusta netti on yksi kaikkien aikojen hienoimmista ja parhaimmista keksinnöistä, koska se voi yhdistää ihmisiä ennennäkemättömällä tavalla, sekä tuoda tietoa lähes kaikkien saataville varsin helposti. Tietysti siinä on ongelmansa, niinkuin kaikessa. On kuitenkin tärkeää opettaa jo lapsia (sekä tietysti myös aikuisia) netin käytössä. Tätä varten pitäisi julkaista kunnollinen netin käytön ja netiketin opas, joka olisi mieluiten ilmainen. Siinä opetettaisiin kriittistä suhtautumista nettiin ja tiedonhakua yms., sekä käytössääntöjä ja järkevän toiminnan suosituksia. Siinä kerrottaisiin siis esimerkiksi, ettei nuoren ole järkevää välttämättä esiintyä netissä omalla virallisella nimellään, eikä välttämättä kannata lähettää kavereilleen tai ladata kuvagalleriaan sellaisia kuvia, joita ei haluaisi kaikkien nähtäville. Oleellista olisi selittää, miksi peruskäytössääntöjä on hyvä noudattaa etenkin netissä (mutta muuallakin). Tähän kuuluu myös hyväntahtoisen tulkinnan periaatteen selittäminen ja perustelu. Tietysti siinä pitäisi kertoa myös lakiasiat, eli mikä on laitonta ja mikä ei. Yhtä tärkeää kuitenkin on kertoa ovelista mainonta- ja manipulointikeinoista, joita netin ja muidenkin medioiden kautta voidaan käyttää.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Median kasvattama

Kuinka minua on mediakasvatatettu

Ala-asteelta muistan kuinka meille hoettiin, että "televisio on hyvä renki mutta huono isäntä". Tämän lisäksi ainoa huomaamani tai muistamani mediakasvatus ala-asteella oli äidinkielen tuntien yhteydessä tehty elokuva. Olin nimellisesti kuvaajana, eli en oikeasti tehnyt mitään. Elokuvan tekemistä ei opetettu mitenkään teoreettisesti, eikä hyvin ylipäätään muuten, vaan kyseessä oli melkeinpä vain kotivideotasoinen yritys. En muista edes koskaan nähneeni tekemäämme "elokuvaa". En tiedä osallistuivatko elokuvakerholaiset (joita saattoi olla joitakin) projektiin enemmän. Muistikuvani mukaan koko projekti oli opetuksen kannalta lähinnä menetetty tilaisuus.

En muista, että peruskoulussa tai edes lukiossa olisi käytetty edes sanomalehtiä opetuksessa, mutta on mahdollista että niin on tehty kerran tai pari. Minkäänlaista kriittisen ajattelun opetusta ei missään vaiheessa meille annettu. Romaaneja peruskoulussa ja lukiossa ohjattiin lukemaan ja niistä kirjoitettiin arvosteluja, mutta mitään kunnon analyysejä ei opetettu tekemään, vaan ilmeisesti opetusta ohjasi usko siihen, että "lukeminen kannattaa aina", kuten erään kirjakaupan mainos on väittänyt. Kyllähän minä mielelläni aina olen kirjoja lukenut, mutta en kyllä välttämättä niitä, joita koulussa käskettiin lukemaan. En ole vieläkään lukenut Seitsemää veljestä. Kalevalaakin olen lukenut mieluummin hieman englanniksi kuin suomeksi.

Ammattikorkeakoulussa opetettiin tekemään kotisivuja, jotain graafistakin muistaakseni, sekä käyttämään tietokoneita ja oletettavasti myös hyödyntämään internettiä. Viimeisimmästä varsin hyödylliseksi osoittautui pian erään kirjan loppuun lisätty netiketti, eli käytösopas internettiin, jota pitäisi kyllä hyödyntää jo alakoulussa.

Avoimen yliopiston tilastotieteen kurssilla sain varmaan ensimmäisen kerran varsinaista kriittisen ajattelun opetusta ja mediakasvatusta, kun lehdissä ilmestyneiden mainosten tilastotieteeseen liittyviä väitteitä arvioitiin. Ehkä jotain samantapaista on saattanut olla jo lukiossa (esim. korkojen ja koron koron laskemisen yhteydessä), tosin ilman todellisia esimerkkejä lehtien sivuilta.

Kuinka media on kasvattanut minua

Tulin maininneeksi, että luen mielelläni kirjoja. Niitä meillä oli kotona paljon (ja luulin pitkään että niin on kaikissa kodeissa), joten oli luontevaa lukea niitä. Enimmäkseen luin kuitenkin aika huonoa kirjallisuutta, jonka ainoa vaikutus sanallisen taidon parantamisen lisäksi varmaankin oli mielikuvituksen kehittäminen. Sanomalehtiäkin meille tuli, mutten ollut niistä kovin kiinnostunut. Aku Ankka ja Tieteen kuvalehti olivat tärkeimmät lehteni nuorena, vaikka myös Time ja Newsweek tulivat jonkun aikaa ja olivat mielenkiintoisia. Englanninkielisiä kirjoja aloin lukea 13-vuotiaana, mikä varmasti kehitti kielitaitoani.

Meille ostettiin ensimmäinen televisio harvinaisen myöhään, kun olin jo ehkä 12-vuotias. Television tai kavereilta lainaamieni videoiden katselua ei rajoitettu muistaakseni ollenkaan. Katselin jonkun verran toiminta- ja kauhuelokuvia, mutta mitään kovin hurjaa (esim. snuffia tai sellaiseksi väitettyä) ei tullut vastaan. Esim. Terminator on edelleen aika hieno elokuva ja pidän naurettavana tapaa, jolla jotkut hurskastelijat ovat sitä kommentoineet. Voi olla, että olin sen verran hyväosainen muuten, ettei katsomillani elokuvilla siksi ollut minuun kovin haitallista vaikutusta, mutta toisaalta on mahdollista, ettei niillä ole sellaista juuri kehenkään. Kielitaitoa TV:n ja elokuvien katselu paransi tietenkin, etenkin sitten kun näköni heikkeni niin, että tekstityksen lukeminen vaikeutui (olin tyypillisen hölmö, enkä hankkinut silmälaseja) - tällöin keskityin kuulemaani ja näkemääni huulten liikkeisiin yms.

Pelasin myös tietokoneella väkivaltaisia pelejä, joita myöskin on syytetty välillä aivan turhaan. Siihen aikaan pelit olivat sarjakuvamaisia, eivät realistisia kuten nykyään. Sillä on varmasti merkitystä niiden vaikutukseen. En tosin ole kovin innostunut nykyisiäkään vastaan esitetyistä syytöksistä. Jos joku väkivallantekijä onkin niitä pelannut, etsisin syitä hänen käytökseensä kyllä aivan muualta kuin hänen pelaamistaan peleistä.

Pelasin jo lapsena myös roolipelejä, joissa väkivalta oli keskeistä. Niillä oli jopa hyödyllisiä kasvatuksellisia vaikutuksia etenkin siksi, että ne herättivät minut ajattelemaan etiikkaa ja metafysiikkaa (vaikken tuolloin näitä termejä edes tuntenut). En tällä kertaa kuitenkaan kerro tästä sen enempää, koska olen juuri tehnyt niin toisaalla.

Internet avasi minulle tien tietoon. Vuosia keskityin jälkiviisaudella arvioiden aivan vääriin asioihin, eli kaikenlaiseen okkulttiseen huuhaa-aineistoon, mutta niiden kautta löysin kuitenkin tieteellisen skeptisismin. Aikani siihen netin kautta tutustuttuani tilasin Skeptical Inquirer -lehden, jonka tilaaja olen edelleenkin. Tämä lehti ja aihepiirin kirjat (sekä jotkut hyvät TV-dokumentit) opettivat minulle enemmän tieteestä ja filosofiasta kuin kaikki koulussa oppimani yhteensä.

On todella surkea tosiasia, että suomalainen koulutusjärjestelmä ei edelleenkään ole merkittävästi tainnut noista ajoista tässä suhteessa parantua, eikä yleisen kriittisen ajattelun ja tieteellisen maailmankuvan kursseja järjestetä edes yliopistoissa juuri koskaan. Erityistieteiden opiskelijat voivat näin hyvinkin valmistua jopa tohtoreiksi asti, oppimatta koskaan yleistämään kriittistä ajatteluaan oman alansa ulkopuolelle. Tästä minulla on ikäviä, henkilökohtaisia kokemuksiakin.

*

Kuten Suorannan, Sintosen ja Kupiaisen artikkelissa "Suomalaisen mediakasvatuksen vuosikymmenet" (teoksessa Kynäslahti, Kupiainen & Lehtonen (toim.): Näkökulmia mediakasvatukseen. Mediakasvatusseuran julkaisuja 1/2007) kertovat, 1980- ja '90-luvuilla tuntuu vallinneen lasten medialta suojelemista painottava käsitys, mutta kovin vahvasti tämä ei meillä kotona onneksi vaikuttanut. Voi vain toivoa, että artikkelissa mainittu medialukutaidon korostaminen vuoden 2004 opetussuunnitelmassa tuo lisää kriittistä ajattelua kouluihin. En kyllä pidätä henkeäni tätä odottaessani.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Koulukiusaamisen uudet muodot

Onneksi ei ollut "sosiaalista mediaa" silloin kun minä olin koulussa, voisi ajatella.

Etsin materiaalia Mediakasvatuskurssin toista välitehtävää varten, ja törmäsin puolen vuoden takaiseen juttuun Hesarissa (tässä vain hieman lyhennetty versio):

Näin kirjoitti Jorma Palovaara 14.4.2011 Helsingin Sanomissa. Täällä koko teksti.

Tämä uusi kiusaamisen muoto on luultavasti tärkein syy antaa (tuleville) opettajille koulutusta mediakasvatuksesta. En ole varma auttaako se, mutta pakkohan sitä on yrittää, koska tuskin moni asia on yhtä tärkeää kuin kiusaamisen poistaminen koulusta.

En ehkä seuraa perinteisiä tiedotusvälineitä kovin ahkerasti, mutta luulen, että juuri nämä kiusausasiat ovat niitä yleisimpiä syitä nostaa mediakasvatus esille. Tosin mediakasvatusta ei välttämättä useinkaan tällä termillä mainita. Tässäkin se mainitaan vain rehtorien puolustuspuheessa, josta jää sellainen käsitys, ettei heillä ole nettikiusaamiseen muita vastakonsteja. Tämän jutun perusteella näyttää siltä, ettei mediakasvatusta ainakaan jutussa mainitussa oppilaitoksessa juurikaan harjoiteta, eikä nettikiusaamisen vastustamiseksi (voida) tehdä mitään muutakaan.

Etsin materiaalia Mediakasvatuskurssin toista välitehtävää varten, ja törmäsin puolen vuoden takaiseen juttuun Hesarissa (tässä vain hieman lyhennetty versio):

Kiusaamisvideot yleistyvät kouluissa

[...] videoiden levittäminen tekee kiusaamisesta entistä rankempaa.Koulukiusaaja levittää yhä useammin uhristaan kuvia tai videoita internetissä.

"Ennen vanhaan lapsi pääsi kiusaajistaan eroon, kun lähti koulusta. Nykyään lasten elämä pyörii niin paljon sosiaalisessa mediassa, että kiusaaminen jatkuu myös vapaa-ajalla ja kotona.""On eri asia, jos lapsi nolataan viiden kaverin edessä kuin joka ikisen koulutoverin edessä. Lapsi miettii, voiko mennä kouluun, jos kaikki nauravat hänelle."HS:n haastattelemien rehtoreiden mukaan asiaa pyritään pitämään kouluissa esillä, ja nuorille annetaan mediakasvatusta.Käytännössä todellisuus näyttäytyy nuorten arjessa erilaisena. HS:n tapaamat Laajasalon yläasteen oppilaat sanovat, että opettajat eivät yleensä tiedä kiusaamistapauksista mitään, eikä oppilaille ole puhuttu yleisistä pelisäännöistä.

Näin kirjoitti Jorma Palovaara 14.4.2011 Helsingin Sanomissa. Täällä koko teksti.

Tämä uusi kiusaamisen muoto on luultavasti tärkein syy antaa (tuleville) opettajille koulutusta mediakasvatuksesta. En ole varma auttaako se, mutta pakkohan sitä on yrittää, koska tuskin moni asia on yhtä tärkeää kuin kiusaamisen poistaminen koulusta.

En ehkä seuraa perinteisiä tiedotusvälineitä kovin ahkerasti, mutta luulen, että juuri nämä kiusausasiat ovat niitä yleisimpiä syitä nostaa mediakasvatus esille. Tosin mediakasvatusta ei välttämättä useinkaan tällä termillä mainita. Tässäkin se mainitaan vain rehtorien puolustuspuheessa, josta jää sellainen käsitys, ettei heillä ole nettikiusaamiseen muita vastakonsteja. Tämän jutun perusteella näyttää siltä, ettei mediakasvatusta ainakaan jutussa mainitussa oppilaitoksessa juurikaan harjoiteta, eikä nettikiusaamisen vastustamiseksi (voida) tehdä mitään muutakaan.

Sanomalehdistä

Lueskelen sitä mukaa kuin ehdin teosta nimeltä Näkökulmia mediakasvatukseen ja pääsin viimein toiseen osaan. Tämä toinen osa alkaa artikkelilla, jossa puhutaan sanomalehtien lukemisesta ja etenkin nuorista sanomalehtien lukijoina. Siinä mainittiin, että 2 % nuorista ei lue sanomalehtiä ollenkaan ja sitten hieman pohdittiin, kuinka nämäkin saataisiin lehdistä kiinnostumaan. Minusta tämän lukeminen toi mieleen puhelinmyyjät, jotka silloin tällöin yrittävät minulle jotain lehteä tai muutamaa kaupitella, eivätkä aina meinaa uskoa, ettei minulla ole varaa sellaisiin. Kysehän ei oikeastaan ole rahasta. Minun pitäisi olla todella rikas, että viitsisin rahojani haaskata tarjottuihin lehtiin, jos silloinkaan. Hieman sama pätee sanomalehtiinkin.

Miksi nuorten, tai ylipäätään kenenkään, pitäisi lukea sanomalehtiä?

Minulle ja varmaan monille muillekin jo ala-asteella yritettiin takoa päähän sanomalehtien lukemisen tärkeyttä. En silti niitä pidä tärkeinä, enkä lue niitä kuin satunnaisesti silloin, kun sopivassa tilanteessa huomaan lähettyvillä lojuvan lehden, eikä ole todellakaan muuta tekemistä kuin sen lukeminen. Siis lähinnä odottaessani vaikkapa luennon alkua.

En vain näe sanomalehtiä kovin hyödyllisinä informaation lähteinä. Niiden sisältö on hyvin pinnallista, eikä yleensä minua kiinnostavista aiheista niissä sanota juuri mitään, tai jos sanotaan, niin todennäköisesti jotenkin virheellisesti. Osaan etsiä webistä niistä asioista paremmin tietoa, kuten myös kirjoista ja (lähinnä akateemisista) aikakauslehdistä.

Sanomalehtien pinnallinen tiedotus on hyödyllistä vain nimenomaan tiedotustarkoituksessa, luulisin. Siis lähinnä jonkin paikkakunnan tapahtumien ja ehkä paikallispolitiikan keskustelunaiheiden kannalta. Artikkelissa paikallislehtien lukemista pidetäänkin tämän takia keinona kotiutua uudelle paikkakunnalle muuton jälkeen. Ehkäpä niin, mutta minulla ei olekaan koskaan ollut tarvetta kotiutua millekään paikkakunnalle (vaan paremminkin esim. yliopistoon - tietysi yliopiston lehtiä voikin pitää niiden paikallislehtinä, jolloin täytyy myöntää että olen niitä käyttänyt juuri tähän tarkoitukseen). Erityisesti maahanmuuttajille paikallislehdet ja ylipäätään uuden asuinmaan lehdet kyllä ovat varmasti todella tärkeitä apuvälineitä kulttuuriin tutustumisessa ja oman paikan etsimisessä.

Mielenkiintoista oli myös artikkelin esiin nostama huomio sanomalehtien lukemisen vaikutuksesta PISA-kokeissa menestymiseen: suomalaisten menestyminen PISA-kokeissa voi selittyä yksinkertaisesti sillä, että monet PISAn kysymykset ovat usein sanomalehtitekstityyppisiä, joiden lukemiseen suomalaisnuoret ovat tottuneet muita keskimääräisesti paremmin. Siis suomalainen koulu ei ehkä olekaan ansainnut saamaansa kiitosta. :)

Miksi nuorten, tai ylipäätään kenenkään, pitäisi lukea sanomalehtiä?

Minulle ja varmaan monille muillekin jo ala-asteella yritettiin takoa päähän sanomalehtien lukemisen tärkeyttä. En silti niitä pidä tärkeinä, enkä lue niitä kuin satunnaisesti silloin, kun sopivassa tilanteessa huomaan lähettyvillä lojuvan lehden, eikä ole todellakaan muuta tekemistä kuin sen lukeminen. Siis lähinnä odottaessani vaikkapa luennon alkua.

En vain näe sanomalehtiä kovin hyödyllisinä informaation lähteinä. Niiden sisältö on hyvin pinnallista, eikä yleensä minua kiinnostavista aiheista niissä sanota juuri mitään, tai jos sanotaan, niin todennäköisesti jotenkin virheellisesti. Osaan etsiä webistä niistä asioista paremmin tietoa, kuten myös kirjoista ja (lähinnä akateemisista) aikakauslehdistä.

|

| Paranormaaleista ilmiöistä, tieteen ja epätieteen rajanvedoista, sekä jonkun verran tiedepolitiikastakin kerrotaan tässä lehdessä. |

Sanomalehtien pinnallinen tiedotus on hyödyllistä vain nimenomaan tiedotustarkoituksessa, luulisin. Siis lähinnä jonkin paikkakunnan tapahtumien ja ehkä paikallispolitiikan keskustelunaiheiden kannalta. Artikkelissa paikallislehtien lukemista pidetäänkin tämän takia keinona kotiutua uudelle paikkakunnalle muuton jälkeen. Ehkäpä niin, mutta minulla ei olekaan koskaan ollut tarvetta kotiutua millekään paikkakunnalle (vaan paremminkin esim. yliopistoon - tietysi yliopiston lehtiä voikin pitää niiden paikallislehtinä, jolloin täytyy myöntää että olen niitä käyttänyt juuri tähän tarkoitukseen). Erityisesti maahanmuuttajille paikallislehdet ja ylipäätään uuden asuinmaan lehdet kyllä ovat varmasti todella tärkeitä apuvälineitä kulttuuriin tutustumisessa ja oman paikan etsimisessä.

Mielenkiintoista oli myös artikkelin esiin nostama huomio sanomalehtien lukemisen vaikutuksesta PISA-kokeissa menestymiseen: suomalaisten menestyminen PISA-kokeissa voi selittyä yksinkertaisesti sillä, että monet PISAn kysymykset ovat usein sanomalehtitekstityyppisiä, joiden lukemiseen suomalaisnuoret ovat tottuneet muita keskimääräisesti paremmin. Siis suomalainen koulu ei ehkä olekaan ansainnut saamaansa kiitosta. :)

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Johdatus mediakasvatukseen

Olen päättänyt opiskella opettajaksi. Pääsin sellaiseen ohjelmaan (Opeksi V), jonka pitäisi valmistaa minut ainakin nimellisesti päteväksi opettajaksi alle vuodessa. Osana näitä noin lukuvuoden kestäviä opintoja on kasvatustieteen perusopinnot, joista Johdatus mediakasvatukseen on piakkoin alkamassa. Tämän kurssin vaihtoehtoisena suoritusvaatimuksena on blogin kirjoittaminen kurssin aiheista. Niinpä kirjoitan niistä nyt jonkin aikaa tähän blogiini. Jossain määrin filosofiaan tämäkin kurssi liittyy, tai filosofia kurssiin oikeastaan, koska filosofia liittyy jotakuinkin kaikkeen. Ainakin jos sen niin päättää ymmärtää. :)

Kurssin ensimmäinen tehtävä oli yllättävän mielenkiintoinen. Yhden päivän ajan täytyi pitää mediapäiväkirjaa, johon merkitsi ylös mitä mediaa käytti mihinkin aikaan. Esim. mitä kirjaa luki, mitä katseli telkkarista, surffasiko netissä jne. Tein tuon tehtävän eilen. Mielestäni katsoin silloin hieman tavallista enemmän telkkaria (TV:stä tallentamaani elokuvaa ja uutiset suorana - näin minulla on tapana toimia, koska en halua katsella mainoksia). Myös Facebookissa tuli tuhlattua aikaa, mutta tämä on ikävä kyllä ollut jonkinlainen trendi viime aikoina. Täytyy yrittää vähentää selvästikin. Tällainen harjoitus voisi olla hyvä kaikkein aina silloin tällöin tehdä, sillä voisi olla hyvä huomata kuinka paljon aikaa tulee tuhlattua aivan vääriin asioihin.

Semmoinen ajatuskin minulle tuli, etten oikeastaan ole varma termin media merkityksestä. Olen tottunut ajattelemaan että sillä tarkoitetaan sellaisia tiedotusvälineitä kuin TV, radio ja lehdet. Siis sellaisia, joiden sisältö tarjotaan julkisesti kaikille halukkaille, vaikkakin ehkä maksua vastaan. Mutta ns. sosiaalisen median (tai web 2.0 kuten sitä joskus harvemmin nähtäväsi nimitetään) kohdalla termin media merkitys tuntuu hämärtyvän. Onko Facebook tiedotusväline? Siis muillekin kuin siellä mainostaville tahoille? Minun statuspäivitykseni siellä näkyvät vain "Ystävilleni", vaikka jotkut muut asiani sielläkin saattavat olla avoimemmin nähtävissä.

Kurssin ensimmäinen tehtävä oli yllättävän mielenkiintoinen. Yhden päivän ajan täytyi pitää mediapäiväkirjaa, johon merkitsi ylös mitä mediaa käytti mihinkin aikaan. Esim. mitä kirjaa luki, mitä katseli telkkarista, surffasiko netissä jne. Tein tuon tehtävän eilen. Mielestäni katsoin silloin hieman tavallista enemmän telkkaria (TV:stä tallentamaani elokuvaa ja uutiset suorana - näin minulla on tapana toimia, koska en halua katsella mainoksia). Myös Facebookissa tuli tuhlattua aikaa, mutta tämä on ikävä kyllä ollut jonkinlainen trendi viime aikoina. Täytyy yrittää vähentää selvästikin. Tällainen harjoitus voisi olla hyvä kaikkein aina silloin tällöin tehdä, sillä voisi olla hyvä huomata kuinka paljon aikaa tulee tuhlattua aivan vääriin asioihin.

Semmoinen ajatuskin minulle tuli, etten oikeastaan ole varma termin media merkityksestä. Olen tottunut ajattelemaan että sillä tarkoitetaan sellaisia tiedotusvälineitä kuin TV, radio ja lehdet. Siis sellaisia, joiden sisältö tarjotaan julkisesti kaikille halukkaille, vaikkakin ehkä maksua vastaan. Mutta ns. sosiaalisen median (tai web 2.0 kuten sitä joskus harvemmin nähtäväsi nimitetään) kohdalla termin media merkitys tuntuu hämärtyvän. Onko Facebook tiedotusväline? Siis muillekin kuin siellä mainostaville tahoille? Minun statuspäivitykseni siellä näkyvät vain "Ystävilleni", vaikka jotkut muut asiani sielläkin saattavat olla avoimemmin nähtävissä.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

The Most Important Teachings of Philosophy

I will list here some of the most important teachings of philosophy that I hope all people (or at least my students) to learn. They are not in a particular order.

- It is most important to learn to cope with epistemic (and other) uncertainty, acknowledging this uncertainty. The feeling of certainty is only psychological and it is an epistemic error. The absolute truth cannot be attained, or even if it can, it is methodologically better to assume that it cannot.

- In addition to known alternatives there are other possible choices. You can also invent new options yourself.

- Aspire to remember all your sources (what have you adopted and from where). That means not only books and movies, but also other people, from whom you have adopted opinions.

- It is important to learn the difference between yourself and the beliefs and opinions you hold (for now). You should not identify with any belief, belief system, or even a way of thinking. Identities are separate from your self, and exchangeable. The Self is a matter of definition. Identities are rarely rationally chosen.

- Critical thinking does not mean being critical of others or of their works. It means being rational, and so also giving critical praise when it is due.

- Criticism is best to be formulated as a question. That will teach also (epistemic) humility. Criticism is very probably erroneous as well, which is worth remebering.

- The Principle of Benevolent Interpretation: Interpret others as if they were ethically, intellectually, and epistemically excellent.

Filosofian tärkeimmät opetukset

Listaan tähän jotain tärkeimpiä filosofisia opetuksia, joita toivon kaikkien (ainakin oppilaideni) oppivan. Ne eivät ole missään erityisessä tärkeysjärjestyksessä.

- Tärkeintä on oppia tulemaan toimeen tiedollisen (ja muunkin) epävarmuuden kanssa, tämä epävarmuus tiedostaen. Varmuuden tunne on vain psykologista ja se on tiedollinen virhe. Absoluuttista totuutta ei voi saavuttaa, tai vaikka voisikin, on menetelmällisesti parempi olettaa että ei voi.

- Tiedettyjen vaihtoehtojen lisäksi on myös muita mahdollisia vaihtoehtoja. Uusia vaihtoehtoja voi myös keksiä itse.

- Pyri muistamaan kaikki lähteesi (mitä olet mistäkin omaksunut). Siis ei vain esimerkiksi kirjat tai elokuvat, vaan myös toiset ihmiset, joilta olet omaksunut käsityksiä.

- On tärkeä oppia ero itsen ja (toistaiseksi) kannattamiensa käsitystensä ja uskomustensa välillä. Ei pidä samastaa itseä ja jotain tiettyä uskomusta, uskomusjärjestelmää, tai edes ajattelutapaa. Identiteetit ovat itsestä irrallisia ja vaihdettavia. Itse on määrittelykysymys. Identiteetit ovat harvoin rationaalisesti valittuja.

- Kriittinen ajattelu ei tarkoita kritisoimista. Se tarkoittaa rationaalisuutta, eli myös kriittistä kehumista silloin kun se on perusteltua.

- Kritiikki on paras muotoilla kysymykseksi. Se opettaa myös (tiedollista) nöyryyttä. Myös kritiikki on hyvin todennäköisesti virheellistä, mikä on syytä muistaa.

- Hyväntahtoisen tulkinnan periaate: Pyri tulkitsemaan toisia niinkuin he olisivat eettisesti, älyllisesti ja tiedollisesti erinomaisia.

Friday, April 1, 2011

Modernism and Religion

I have finally finished reading Moojan Momen's book The Phenomenon of Religion. A Thematic Approach (Oneworld Publications, 1999), a good popular introduction to comparative religion. I have posted several times in this blog about various chapters in that book before, and now is the time for the last one.

Momen writes about the insights of Wilfred Cantwell Smith on the study of religion:

The 'religiosi' were monks or hermits in the past, but everyone (except perhaps some very rare individuals) seems to have lived within the conceptual world of religion simply because there was no alternative. People usually just accept their traditions as the way things have always been done, even if those traditions are really just a generation or two old. They go by their daily lives without bothering to think too much. They perform the usual rituals, because that's just what they've been accustomed to doing.

Knowledge of the scientific worldview, and the awareness of the sheer plurality of religions and different worldviews (no longer just in some distant countries, but even in one's own) makes it impossible for people pretty much anywhere to simply implicitly assume that their traditional religious worldview is true. They force people to recognize the fact that others don't believe what they believe. Especially in the West, knowledge of historical religions, such as the polytheisms of Antiquity, forces people to acknowledge that as the ancient religions are discarded as false, so can theirs. Science is pushing all gods out or its worldview, and at least educated people accept the superiority of science as a truth seeking method. One can only hope people will also learn to think scientifically (critically), and eventually to discard the last vestiges of religion. This, of course, is what intellectuals have for a long time thought would occur very soon.

The response to the advancement of "Western" Christian and then secularized culture has been a problem for other cultures it has come to contact with:

For the present, the clash of the "two cultures", that of the "West" with that of the Islamic culture, is of present concern:

The teaching of the scientific way of thinking itself is inherently dangerous to the traditional worldview because in its progressivism it is so contrary to the religious, conservative way of thinking. It teaches the student to not be dogmatic, to not accept anything without proper justification. This is detrimental to religious faith more than anything else. It is no wonder that the religious (especially the fundamentalists) want to take use of all the fruits of science and technology, without accepting source of those innovations, the science itself. They try to retain their superstitious worldviews by refusing to accept the scientific worldview, but how long can they resist? Perhaps their verbal and sometimes physical violence is actually caused by their desperation in the face of certain extinction?

But there is also the recent resurgence (or death growl?) of fundamentalism, even in the West. The US is the leading country in Western religiosity. In fact, it is a strange exception to the general development of secularization. Americans are surprisingly religious, while Europeans and other "Westerners" tend to be almost non-religious, and certainly becoming less religious. As explained in a great article in Free Inquiry (or was it Skeptical Inquirer?) some years ago, this is probably due to such social differences as the lack of real social security in the US, combined with a highly competitive and individualistic culture. These leave the individual rather helpless and at the mercy of fate, compared to the situation in European welfarestates, for example. When nothing else can be done, the resorting to religious wishful thinking is understandable.

The trend could be changed by the failure of the welfarestate systems under the pressure of global economic powers, climate change, and other events and things uncontrollable by the people in European and other countries. It could spell disaster for us. Religion could rise to power again, at the worst possible time, resulting in the destruction of all the good things we have achieved, such as (more or less) secular states that (more or less) uphold humanrights, provide high quality education for the masses, and support the progress of science. It is possible that mankind, and science with it, will perish in the near future. To avoid this, we must actively seek ways to educate each other, and to find rational solutions to our problems.

Religion has a strong hold of American politics not only because of the lack of social security, but also because the powerful use of the media by religious individuals and organizations:

And as anyone reading this (if anyone is actually reading this), things have only gotten worse since the 1980s in the US.

Momen writes about the insights of Wilfred Cantwell Smith on the study of religion:

What we now call the religions of the world were [...] not always seen thus. [...] In the pre-modern world, religion was not a separate part of life that could be analysed as an entity. Rather, it was intergral to living; it was the way that people saw the world. Since what we now call the religious view of the world was the way that people saw the world, it was, in a sense, invisible, part of the basic assumptions that people made about life and the world about them. These assumptions were so basic that they were not a subject for discussion, they were accepted as 'given', forming an inherent and seamless part of people's reality. What the modern world has done is to separate this part of human life and call it religion.

[...] The use of the word 'religion' itself, in its sense of differentiating the different religions of the world, is a new usage. In earlier times its meaning was closer to the present use of the word 'piety'.

(P. 475.)

The 'religiosi' were monks or hermits in the past, but everyone (except perhaps some very rare individuals) seems to have lived within the conceptual world of religion simply because there was no alternative. People usually just accept their traditions as the way things have always been done, even if those traditions are really just a generation or two old. They go by their daily lives without bothering to think too much. They perform the usual rituals, because that's just what they've been accustomed to doing.

Each religion is now seen as one of a number of competing religions, and even these must struggle for people's loyalty with a large number of modern ideologies and worldviews.

[...] Religion has lost its claim to be the exclusive viewpoint from which people see the world.

(P. 476.)

Knowledge of the scientific worldview, and the awareness of the sheer plurality of religions and different worldviews (no longer just in some distant countries, but even in one's own) makes it impossible for people pretty much anywhere to simply implicitly assume that their traditional religious worldview is true. They force people to recognize the fact that others don't believe what they believe. Especially in the West, knowledge of historical religions, such as the polytheisms of Antiquity, forces people to acknowledge that as the ancient religions are discarded as false, so can theirs. Science is pushing all gods out or its worldview, and at least educated people accept the superiority of science as a truth seeking method. One can only hope people will also learn to think scientifically (critically), and eventually to discard the last vestiges of religion. This, of course, is what intellectuals have for a long time thought would occur very soon.

Towards the middle of the twentieth century, the outlook seemed bleak for religion. Many scientists and sociologists were prepared to foretell its demise, either over a few generations or over the next few centuries. (P. 484.)

The response to the advancement of "Western" Christian and then secularized culture has been a problem for other cultures it has come to contact with:

The arrival of the Western powers in most parts of the world during the nineteenth century brought with it severe problems for the religions of those places. The technological and political superiority of the West appeared to lay down an unanswerable challenge to the established religions of other parts of the world. (P. 490.)

For the present, the clash of the "two cultures", that of the "West" with that of the Islamic culture, is of present concern:

For the Middle-Eastern Muslim in the nineteenth century, this dilemma could be expressed thus: if the religion of Islam is the true religion of God, why has God allowed the Muslim nations to fall so far behind the Western, Christian nations? One partial solution to the dilemma appears to be a wholesale adoption of modernity so as to close the gap. It is, in particular, modern technology that is imported -- this being something that does not inherently challenge the religious worldview. But along with modern technology comes modern education, to enable people to use the technology. Thus, gradually, there arrive otehr modern concepts such as democracy and individual rights. These are much more challenging to traditional society, its structures and, ultimately, its religious foundations. (P. 490.)

The teaching of the scientific way of thinking itself is inherently dangerous to the traditional worldview because in its progressivism it is so contrary to the religious, conservative way of thinking. It teaches the student to not be dogmatic, to not accept anything without proper justification. This is detrimental to religious faith more than anything else. It is no wonder that the religious (especially the fundamentalists) want to take use of all the fruits of science and technology, without accepting source of those innovations, the science itself. They try to retain their superstitious worldviews by refusing to accept the scientific worldview, but how long can they resist? Perhaps their verbal and sometimes physical violence is actually caused by their desperation in the face of certain extinction?

But there is also the recent resurgence (or death growl?) of fundamentalism, even in the West. The US is the leading country in Western religiosity. In fact, it is a strange exception to the general development of secularization. Americans are surprisingly religious, while Europeans and other "Westerners" tend to be almost non-religious, and certainly becoming less religious. As explained in a great article in Free Inquiry (or was it Skeptical Inquirer?) some years ago, this is probably due to such social differences as the lack of real social security in the US, combined with a highly competitive and individualistic culture. These leave the individual rather helpless and at the mercy of fate, compared to the situation in European welfarestates, for example. When nothing else can be done, the resorting to religious wishful thinking is understandable.

The trend could be changed by the failure of the welfarestate systems under the pressure of global economic powers, climate change, and other events and things uncontrollable by the people in European and other countries. It could spell disaster for us. Religion could rise to power again, at the worst possible time, resulting in the destruction of all the good things we have achieved, such as (more or less) secular states that (more or less) uphold humanrights, provide high quality education for the masses, and support the progress of science. It is possible that mankind, and science with it, will perish in the near future. To avoid this, we must actively seek ways to educate each other, and to find rational solutions to our problems.

Religion has a strong hold of American politics not only because of the lack of social security, but also because the powerful use of the media by religious individuals and organizations:

In 1960,the Federal Communications Commission, the government organ that controls broadcasting in the United States, issued a ruling that meant that local radio and television station owners could charge for religious broadcasting and still have it count towards their public interest broadcasting commitments. The mainstream churches, who had until then dominated the media, refused to purchase broadcasting time. The evangelical movements enthusiastically picked up the vacant slots. From that time onwards, it has been evangelists who have dominated religious broadcasting in the United States.

[...] By the 1980s, the televangelists were building churches and universities and funding such projects as theme parks with the money being raised by their broadcasts. In addition, several televangelists began to move into the political arena. Pat Robertson's Christian Coalition and Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority supported both of Ronald Reagan's presidential campaigns and were credited with delivering a large block of votes to him.

(P. 521.)

And as anyone reading this (if anyone is actually reading this), things have only gotten worse since the 1980s in the US.

Friday, March 25, 2011

Fundamentalism and Liberalism

I am still reading Moojan Momen's book The Phenomenon of Religion. A Thematic Approach (Oneworld Publications, 1999), and blogging about what I find interesting in the book. Before starting to read this book, I wrote about what I read in another book about Fundamentalism and Modernism in Islam. The title of this text is taken from chapter 14 in Momen's book. It should be obvious that I am very much interested in this subject, and so will quote much of that chapter here. Momen begins by explaining the importance of the topic:

One aspect of religion that has come to general attention in recent years has been the upsurge of fundamentalism. The split between fundamentalists and liberals appears to affect almost every religious community to one extent or another, in many different countries. Almost every religious movement, other than the most narrow sects, contains individuals who tend towards either extreme. (P. 363.)

It is often thought that the term 'fundamentalism' cannot be applied to religions other than Christianity. This is due to the history of the term, as Momen notes before defining the term for wider usage:

Historically, many authorities date fundamentalism from the publication in North America of a series of pamphlets, The Fundamentals, between 1910 and 1915. Although to trace the name to this event would be correct, to date fundamentalism from it would be a very limited view of a phenomenon that has a long history in religion. Also limited is the opinion that fundamentalism is a reaction to modernity. This view would restrict the occurence of fundamentalism to modern times (although it must be admitted that modernity has brought fundamentalism very much to the fore). Nor, indeed, should fundamentalism be limited to Christianity or even the Western religions. (P. 363.)

The point is that the phenomenon referred to as fundamentalism is much wider than one religion (or even religions in general), so it makes sense to define the term in a way that allows the student of religions to use it in a wider scope. Momen goes on to analyze the characteristics of both fundamentalism and liberalism, in order to show what kind of phenomenon (or phenomena) we are trying to understand. First, he looks at the attitude toward "holy" scriptures: